What's up with climate

Working in climate science has been an interesting journey. It is a field that is extraordinary in that communication and societal impact plays a crucial role. This, in our polarized world, unfortunately leads to a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding: from complete denial to extreme forms of alarmism. As someone who has worked on climate science for 3 years, I will try to give my view on the situation. I am not currently involved in Earth systems, but I have had a pleasure to interact with these people. So what is the state of climate, and where are we going? What are the counter-intuitive mechanisms of climate change, and what can we do about it? How much worried should we be and what is helpful to do?

What’s the problem doc?

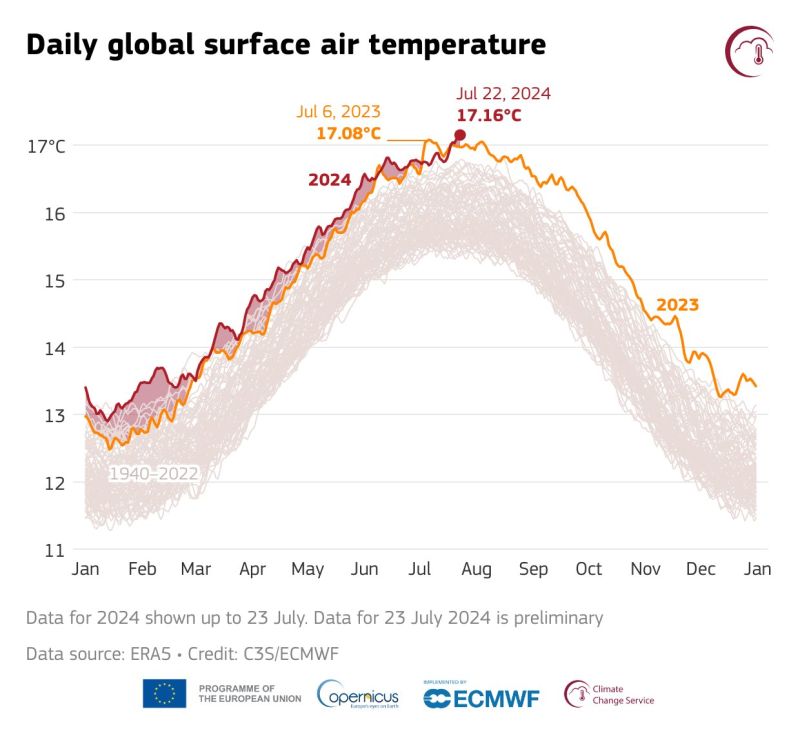

We start from a graph of temperature as usual, but not the most usual one. The figure below comes from Copernicus and shows the trends in temperature change. It illustrates vividly that the last two years have been indeed exceptional. Of course, the more common graph to show is that one which shows the global temperature spike since the industrial revolution, so I omit it here, since most readers have probably seen it.

It should be noted that there are three factors that potentially explain this anomaly, and they will be covered in the following sections. But before doing this we will have to answer some important questions.

What is climate?

Climate corresponds to the long-term average of weather. Weather is the day-to-day state of the atmosphere, while climate is the average of weather over a long period of time. Climate is a complex system that is influenced by both natural factors and human activities. Many of the processes take time on different scales, such as decades, centuries, millennia, and even longer. Climate change can have a wide range of impacts on the environment, including global and regional changes in average temperature, sea levels, frequency or severity of precipitation patterns and storms.

Is climate predictable?

How reliable is weather forecast few weeks in advance? Not at all, actually. But how can we then be certain that what we say about climate change will happen? To illustrate this point consider the famous Lorenz butterfly below:

The Earth system including oceans, atmosphere and soil is chaotic, which means that it is sensitive to initial conditions and small perturbations can lead to large changes in the outcome. This is why weather forecasts are only accurate for a few days. However, climate is a statistical quantity, and it is possible to make predictions about the long-term average of weather. What emerges is that climate is less predictable on the scale of years, becomes somewhat predictable on the scale of decades and more predictable on the scale of centuries. This statement has to be qualified as here I am talking about linear response of the global climate system. There are many non-linear processes that can lead to abrupt changes that are more difficult to predict, such as the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) that I will talk about later.

What causes climate change?

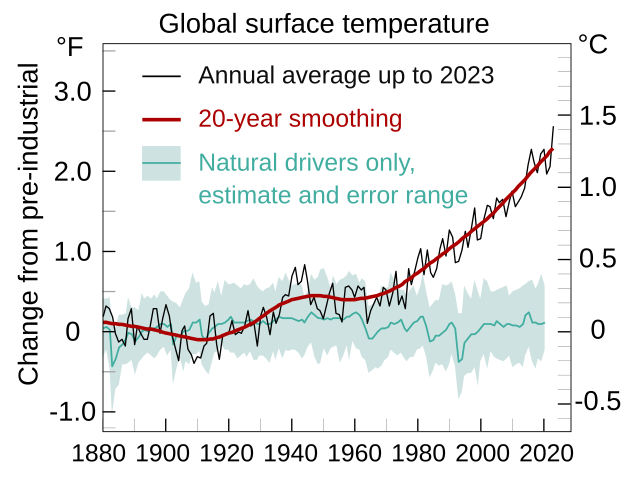

Climate change can be caused by natural factors, such as volcanic eruptions and solar radiation, or by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels. Crucial thing to understand about the energy balance of Earth is that while it is primarily driven by the sun, much of the energy reaching the Earth is absorbed by the surface and then re-radiated as heat. Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere trap some of this heat, preventing it from escaping into space. The classic question is how much does the average temperature change if we double the amount of CO2 which is one of the primary greenhouse gases. Simple calculations of radiative transfer in the column of atmosphere show that the direct effect of CO2 would only explain a third of the observed warming. So where does the rest come from?

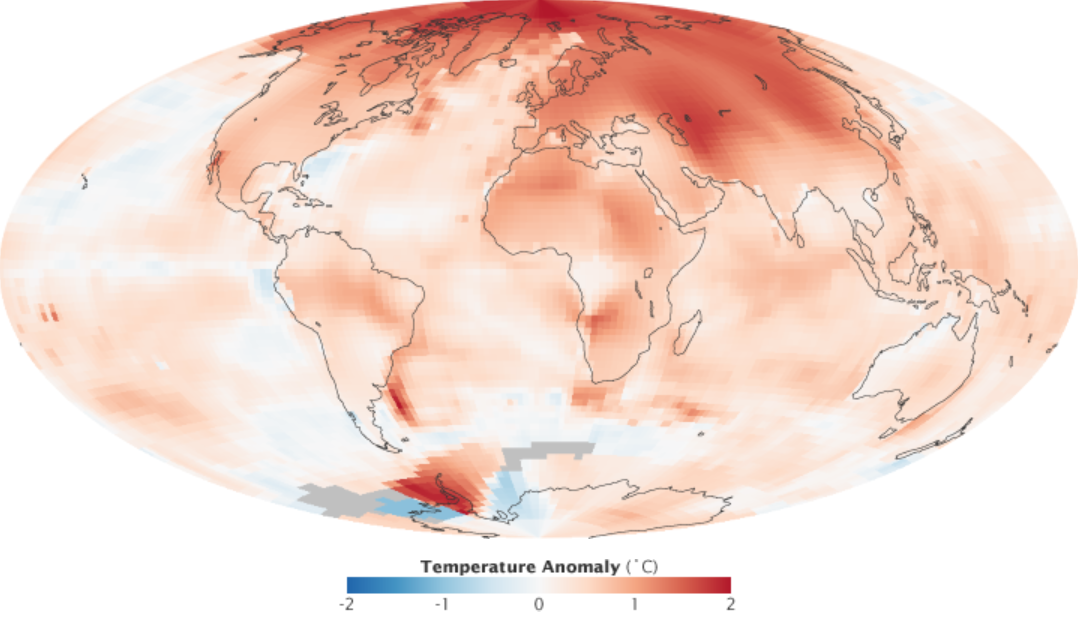

To understand another third we have to remind ourselves that from thermodynamics we know that increasing the temperature of the air allows it to hold more moisture: water vapor is also a very potent greenhouse gas, in fact, more so than CO2. But the atmosphere has a natural way of getting rid of it if there is too much, while CO2 must be sequestered through biomass/ocean acidification or other chemical processes. Some of these processes take much longer, thus making the problem of stray CO2 so acute. Thus, CO2 increases temperature by trapping heat, allowing the air to hold more water vapor further increasing temperature. There is actually an optimal amount for a given amount of CO2 thus we can say that water vapor feedback leads to 100 percent more warming than one would expect simply from CO2. No one in scientific literature disputes these 2/3 of warming. There is also ice-albedo feedback which is a positive feedback mechanism: as the ice melts, the Earth’s surface becomes darker, absorbing more heat and causing more ice to melt. This leads to faster warming of the poles compared to equatorial regions which is observed. In addition, there is a poleward heat transport that arises which further contributes to the so-called “Arctic amplification” effect relating to this poleward warming.

The situation becomes much more complicated once we factor in the clouds and aerosols. Clouds can both reflect sunlight back into space, cooling the Earth, and trap heat, warming the Earth. The net effect of clouds, especially in future warmer atmosphere, is still not fully understood. Indeed, clouds are the main source of uncertainty in climate models and the climate scientists are quite open about this. Nevertheless, most climate scientists agree that the net effect of clouds on global warming is likely positive.

Notice that in addition we observe the sun very carefully, and we know that Earth’s warming is not due it. The climate science makes a prediction that the warming must occur in the lower atmosphere (troposphere), while the upper atmosphere (stratosphere) must cool. This is exactly what we observe. Many of the global predictions of climate change and some regional predictions have been confirmed by observations, which is a strong evidence that the basic mechanism described here forms a consistent theory of climate change.

Can we draw conclusions from climate models?

Climate models are a tool that is often employed by climate scientists to represent current past or future climates. They exist in different varieties from very simple single column models to very complex global Earth system models that are required to couple the atmosphere, ocean, land, and ice. The models are based on the fundamental laws of physics, such as the conservation of energy and mass, but certain small-scale processes cannot be accurately represented, specifically the ones smaller than tens of kilometers in size, that typically corresponds to the spatial resolution of the models. A good rule of thumb is that the models are reliable on global scale and less so on regional scale.

So to summarise, the primary cause of global warming is the increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which is caused by human activities such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation. This conclusion can be made with climate models of different complexity, observational record, basic physical principles and the results are consistent when it comes to global temperature anomaly. This is why the scientific community attributes the observed climate change to human activities despite apparent deficiencies of the models in predicting small scale weather events.

What do we not know for sure?

IPCC reports are an attempt to provide detailed information and quantify uncertainties in the projections. They attempt to provide meta-analysis of the scientific literature to provide the most reliable assessment by the expert panel about the state of the climate and its likely evolution that could be useful for the policymakers. IPCC reports also make regional projections, for instance about the state of future climate in areas such as South- East Asia where many of the areas are projected to become unlivable due to heat stress. Such circumstances could lead to massive migration which could be destabilizing. Also, attention is paid to changes in precipitation patterns, which could lead to droughts and floods. The reports also discuss the impact of climate change on biodiversity, agriculture, and human health: adaptation and mitigation.

As mentioned earlier, while major trends such as linear response of the climate system to the CO2 driving are understood, there are some wild cards, if you will, which may have significant impact, but we don’t know if and especially when they will happen. One such wild card is Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which is a large system of ocean currents that transports warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic. The AMOC is driven by differences in temperature and salinity, and it plays a crucial role in regulating the climate of Europe. The AMOC has been weakening in recent years, and there is some evidence that it may be close to a tipping point where it could collapse. If the AMOC were to collapse, it could lead to a rapid and severe cooling of Europe, which would have major impacts on agriculture, energy production. The consensus of climate scientists is that the collapse of AMOC is unlikely in this century, but it is not impossible and there are routinely pre-prints on arXiv that discuss this possibility even before the year 2050. Actually, I have met a well-respected climate scientist publishing on this topic, Hank Djikstra.

Can we blame oil industry for hurricane Katrina?

Another buzzword that is commonly discussed in the climate outreach is extreme weather events. Events such as AMOC are difficult to ascertain because many of the relevant processes are not included in models. On the other hand, extreme events such as heatwaves routinely occur and clearly display increasing frequency. It is not hard to make even causal connection between the warming of the Earth and the increased frequency of heatwaves. This factor indeed puts more stress on society and agriculture, although it is easier to deal with both in developed countries. However, it is much harder to make a causal connection between the warming of the Earth and a particular hurricane. The reason is that hurricanes are complex systems that depend on many factors, such as sea surface temperature, wind shear, and atmospheric moisture. While it is true that warmer oceans can lead to more intense hurricanes (because the processes of hurricane generation is akin to a heat engine), it is difficult to say that a particular hurricane was caused by climate change. This is why the IPCC reports are careful to say that climate change is likely to increase the frequency of some extremes, but it is difficult to say that a particular one was caused by climate change. Also, we should note that the definition of the extreme event (e.g. what is a heatwave) is not always clear and can be subjective. Typically, some threshold is chosen, however it might be that if we were to choose a different threshold we would get a completely different result. What makes things even more complex is that the impact of extreme events is not only determined by the event itself, but also by the vulnerability of the population and the infrastructure. To give an example, California has been experiencing droughts recently, as well as wildfires. While global warming could also play a role, the wildfires are also caused by the fact that in California people are increasingly building houses in areas that are prone to wildfires and that for about century or so the policy has been to suppress fires which has led to accumulation of forest fuel thus leading to uncontrollable fires.

Nevertheless, the field of extreme event attribution is a new emergent field and I have worked with people involved in it. The idea is to not only rely on climate model projects but also apply statistics and data analysis to the observed trends.

Is it only global warming to blame?

We record exceptional loss of biodiversity. Climate change will become a major factor in the loss of biodiversity. One of the recent effects that had an impact on biodiversity is the coral bleaching. Coral bleaching is caused by the warming of the oceans, which can lead to the death of the coral reefs. Coral reefs are important ecosystems that provide habitat for many species of fish and other marine life, and their loss can have a major impact on the health of the oceans.

Nevertheless, at the moment the primary cause of this loss is habitat destruction, which is caused by human activities such as deforestation, urbanization, and agriculture. Thus, even if we were to curb emissions today, we would still have to deal with the loss of biodiversity. That does not however mean that we should not curb emissions.

What about the anomalous temperature 2023-2024?

The figure in the beginning of the post shows that the last two years have been exceptional. There are three factors that potentially explain this anomaly. The first factor is the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is a natural climate pattern that occurs in the tropical Pacific Ocean. During an El Niño event, the surface waters of the Pacific Ocean become warmer than usual, which can lead to changes in weather patterns around the world. The second factor is the global warming trend which we talked about above. The third factor is interesting because it is potentially related to the unusually warm Atlantic ocean temperature in 2023 and specifically the cause behind this, which is believed to be reduction in man-made aerosols. There were some regulations that were put in place to curb emissions by the ship industry, and some scientists believe that the resulting reduction in aerosols blocked less sunlight that was able to reach the ocean and thus lead to access heat. This is interesting, because overall concern about pollution may have lead to this unintended effect. However, it is important to note that the extent of the warming in 2023-2024 is still being studied, and it is not yet fully understood.

Possible solutions

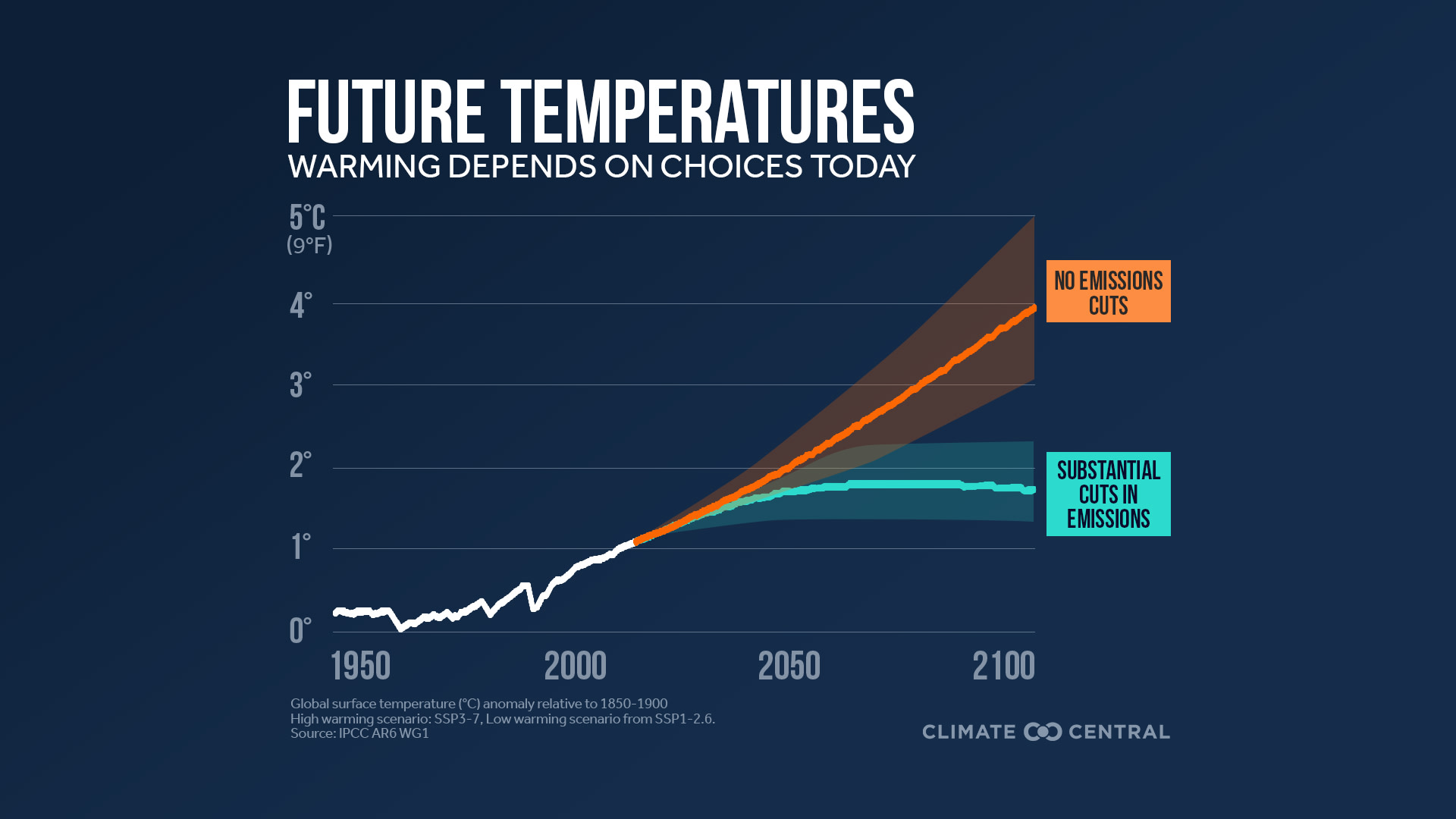

The situation that I described in this blog post is often now labelled “climate crisis” or “climate emergency”. I am not here to debate the utility of this nomenclature, however it is clear that the situation is getting worse every decade if we don’t act. This is because in addition to having traditional emitters in the developed world, we will have soon a lot of new emitters from the developing world, who have not contributed yet to the major part of the total carbon emissions in the absolute terms. However, they are too poor to develop green sector, so it falls on the shoulders of the developed world to help them. I am not advertising here for immediate net zero policy since if we were to stop all emissions today we would have economic crisis on our hands and starvation. The idea is to gradually approach via targeted set of investments in green sector. Already solar energy is cheapest for of energy, although still remains intermittent and would require development of better storage capacity. However, I would also point to the importance of keeping the nuclear energy in the mix, rather than phasing it out like Germany did. In addition, there are sectors of economy that are difficult to decarbonize, such as aviation, and we will have to rely on carbon capture and storage. There are also individual steps that we could take to reduce emissions, such as reduce consumption of meat, which to me appears as a less radical and more feasible step.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: