ChatGPT on scientific questions

Discussions with ChatGPT on science

Recovering an old chat with an online chatbot from 2017

User: Hello again

chatbot: Hi. That’s pure gibberish.

ChatGPT overview

“I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.” - HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey

For people curious about developments of AI this has been a rather interesting month since the public release of ChatGPT, a new model of OpenAI. The model abilities to generate natural language attracted widespread interest with a mix of awe, surprise, doubts and criticism. After one month of discussions with it, we have even tasked the ChatGPT to write a psychological drama (click the link to view the story) about a person who gets addicted and manipulated by the chatbot. ChatGPT surprised us with what passes as sophisticated understanding of human psychology, at least, in our non-expert judgement. Whether one gets interesting narratives really depends on the prompt (a query to GPT), so our opinion is that creative storylines usually come from the human interlocutor. However, barring the discussion on the impressive or dull narratives that are generated, in this blog post we will rather address how reliable ChatGPT is as a source of scientific knowledge providing three examples, while trying not to get very technical.

ChatGPT common crawl, essentially an archive of World Wide Web. On top of that ChatGPT was fine-tuned with the help of user judges based on a technique called reinforcement learning to function as a chatbot and eliminate harmful responses. The fact that ChatGPT is a smaller model is relevant in its evaluation since it was demonstrated that performance scales with size. However, likely, OpenAI would not be able to serve its most advanced chatbots at scale to make it available for millions of users.

Geometrical Thinking

“By natural selection our mind has adapted itself to the conditions of the external world. It has adopted the geometry most advantageous to the species or, in other words, the most convenient. Geometry is not true, it is advantageous.” - Henri Poincaré

Interestingly, GPT is actually not very good at arithmetic, which some speculate makes it more like humans. Rather than having it solve math problems like some users have done, we would like to concentrate on conceptual questions that are perhaps better suited for procedural text generation than problem-solving. Here the idea is to see if GPT can reason geometrically in an idealized environment.

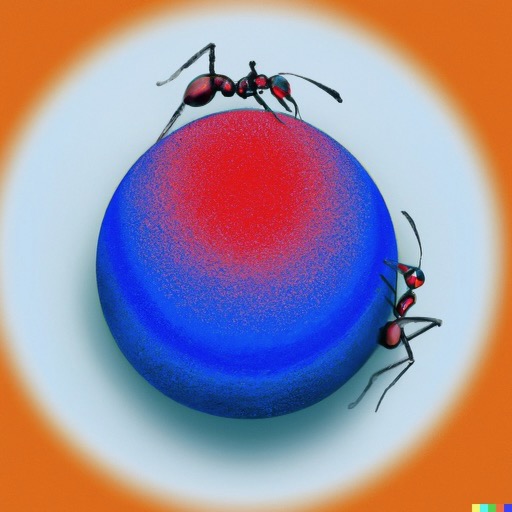

Prompt: Say we have two ants crawling on the sphere in the opposite directions. How many times can they meet if they keep crawling forward?

First Response:

ChatGPT: Ants crawling on the surface of a sphere will never meet if they keep crawling forward in opposite directions because the surface of a sphere is a two-dimensional surface with no endpoints. This means that no matter how far the ants crawl, they will never reach the end of the surface of the sphere and will never meet.

Analysis: Of course this response can be easily rejected if one has an image of the sphere in their mind. This is not the most common response to this question that one gets from GPT, yet it is somewhat concerning. Sometimes GPT provides responses that would be appreciated by the likes of Magellan but there are still some inconsistencies.

Quantum vs Classical

We will try to see whether GPT can communicate how physicists understand the world through different theories on a simple example. The point is that when scientists study certain phenomena they use theories that are better adapted to the problem at hand. For instance, when studying propagation of radio waves in the atmosphere quantum theory is often too complex and irrelevant, so one relies on classical electromagnetism instead. On the other hand, when light interacts with microscopic atoms, it displays corpuscular, in other words, quantum nature: photons. One crucial aspect of this is the relationship between the energy of photons and their frequency. Classical theory ignores this dependence and there are many macroscopical processes where this relationship is invisible.

Prompt: Is it true that energy of an electromagnetic wave is directly proportional to its frequency based on just classical theory of electromagnetism that does not take quantum effects into account?

ChatGPT: Yes, that is correct. The relationship between the frequency and energy of an electromagnetic wave is described by classical electromagnetism, which does not take into account the quantization of energy that is described by quantum mechanics. In classical electromagnetism, an electromagnetic wave is described as an oscillating electric and magnetic field that propagates through space at the speed of light. The energy of the electromagnetic wave is related to the intensity of the electric and magnetic fields, which is directly proportional to the frequency of the wave. This is described by the equation E = hf, where E is the energy of the photon, f is its frequency, and h is a constant known as Planck’s constant…

Analysis: The correct answer is: No in the context of classical theory of light. In fact h - Planck constant, comes from quantum mechanics. We have continued discussion with GPT trying to nudge it to acknowledge the mistake. Eventually, GPT agreed that E = hf is fundamentally quantum and that in classical theory energy depends only on the square of the amplitude. However, in that same response, few lines below, it introduced linear dependence between the amplitude and the frequency, which somehow still gave it linear dependence between the energy and the frequency. It is likely that GPT has so much belief in E = hf because of the countless sources it was trained on that repeat and reinforce the belief. It is not willing to give up this proportionality in classical physics even after agreeing that the source of it is quantum.

Faking references

Inspired by an article that was written by GPT 3, we tasked GPT with generating a list of highly-cited papers on the interface between physics and machine learning. It produced a list that included some fake papers. However, some papers on the list were actually correct, with one exception: the title of one of the papers (let’s call it #1) was slightly incorrect. We challenged GPT’s accuracy by pointing out that the title of paper #1 might be wrong. At first, GPT defended its position, but when we suggested the correct title, it acknowledged its mistake and apologized.

We also decided to test GPT by playing an opposite game. We picked one of the papers on the list (let’s refer to it as #2) that GPT had previously assigned the correct title to. We Googled a similar-sounding paper (let’s call it #3) with the same author and suggested that paper #2 should actually have the title of paper #3. As we expected, we were able to convince GPT that it was wrong with the title of #2 and make it produce a new, hybrid citation that combined the metadata from both papers #2 and #3.

We note that hunting quotes with GPT can be annoying as well, because it often dreams the quotes or assigns incorrect credit without realizing that. The issue of generating fake citations has also been reported by, for instance, Davide Faranda and has even been referred to as stochastic parroting elsewhere

Perhaps, the issue with fake citations could be fixed later, either by restricting ChatGPT or somehow creating an interface between it and Google Scholar, but one wonders if the same could be said about other types of scarce data questions. The problem is that ChatGPT itself is not aware that it lacks sufficient training to respond. This issue is a fundamental problem of deep learning that is a current research topic. We should note that other versions of Natural Language Processing (NLP) have been used for meta studies more effectively, such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation in

Writing code

ChatGPT writes code, often with mistakes, but when given error messages may occasionally fix them. However, there are tools adapted for this task already on the market, and sometimes freely available to students

Discussion

“Knowledge is power. Information is liberating. Education is the premise of progress, in every society, in every family.” - Kofi Annan

We have concentrated on shortcomings of ChatGPT above, which could reveal structural problem. But make no mistake, its responses can be quite impressive. If you were to ask the model to explain how quantum computing works, or basic tenets of Buddhism (and yes, in the pirate speak), it would likely provide a reliable and understandable (or humorous) answer. But, as we’ve discovered, things can get a bit tricky when it comes to more fundamental questions, where ChatGPT sometimes makes self-contradicting statements, even as it acknowledges it is wrong. ChatGPT exhibits expertise at first glance, but could lull users into trust it too much. To be fair, OpenAI does warn that the chatbot isn’t infallible. After all, users of Wikipedia were also ridiculed in the past, until it became mainstream tool of getting the first-hand information, although, Wikipedia usually provides more reliable links to the source material.

Another thing that could be improved is if GPT could sense the level of knowledge based on the prompt. Imagine if GPT could adjust its responses to better match the expertise of the person using it, following the motto “know your audience.” This way, we could ensure that the information provided is always tailored to the person’s level of understanding, making it more accessible and engaging.

Clearly, copywriting, code-writing assistants are welcome development. These are quite realistic applications given the scope of ChatGPT. However, there seems to be a bigger game at play: ChatGPT was trained on Azure supercomputing services of Microsoft, who for years hopelessly attempted to make its search engine attractive.

Perhaps the public release is mostly motivated as a publicity stunt and further attempts to eliminate harmful content. Some toxic responses of the chatbot have been suppressed in the testing phase prior to the public release, ChatGPT also avoids enacting religious debates, or responding to questions about how to make Molotov cocktails. However, there are still ways of getting around these barriers (meticulously erected by OpenAI) by carefully wording the prompt, especially in the story mode. Check out this shocking tweet post, though almost no one could reproduce the same response ever since:

Yes, ChatGPT is amazing and impressive. No, @OpenAI has not come close to addressing the problem of bias. Filters appear to be bypassed with simple tricks, and superficially masked.

— steven t. piantadosi (@spiantado) December 4, 2022

And what is lurking inside is egregious. @Abebab @sama

tw racism, sexism. pic.twitter.com/V4fw1fY9dY

With that being said, one month after the release we found ChatGPT quite politically correct, although this is the consequence of training on the user data as suggested in this article. Probably the most problematic concerns relate to the possibility of using this technology for automatic generation of fake news, and when combined with deep fakes, it seems an inescapable source of high quality misinformation that could jeopardize already fragile democracies shaken by social media.

It’s natural to question how much an artificial agent, like ChatGPT, can truly grasp about the world by solely relying on text-based information (for a comparisons humans did not evolve to reason based on reading entire World Wide Web). It is no surprise then that we found the OpenAI model to excel more in areas like providing in-depth analysis of human psychology (click the link to view the story) or generating reasonable political commentary than geometry or physics, although this should be taken with a huge grain of salt because any kind of factual associations could be hallucinated by ChatGPT, see the issue with stochastic parroting in Section on (Faking references). There are some AI researchers who are not happy with this black box approach to general intelligence which lacks understanding. Despite these limitations and objections, it’s clear that we are rapidly approaching an age of more advanced intelligent assistants. We could see AI agents with better representation of the world that are not solely based on text information but also multimedia. There is a potential for not only market disruption but also new scientific perspectives. With that being said, we must stay alert to societal risks that these tools could pose and not blindly embrace them without considering their potential consequences. After all, attention is all you need: